Part I: Thelemic Philosophy

Prologue: Foundations

Chapter 1: Epistemology

Chapter 2: Metaphysics

Chapter 3: Ethics

Chapter 4: Politics

Epistemology

While metaphysics will tell us about the nature of the universe in which we live and the experience we accumulate as a matter of our existence, a detour must be taken in order to understand the validity domains of how we process experience. To do this, we must examine epistemology as informed by the Law of Thelema and why this is our first branch of discovery rather than jumping directly into metaphysics.

Epistemology is, simply put, the study of knowledge. I have avoided the distinction between epistemology and gnoseology due to the over-reliance and abuse of the word 'gnosis' in modern occult circles. While there is a difference, it's not enough at this stage of examination to split hairs over the distinction.

In Thelema, epistemology could be approached as self-discovery. While there is some throwback to metaphysics here—every man and every woman is a star; each individual is the center of their own universe; &c—it is important to understand how it is that we gather knowledge of ourselves, of each other, and of our environment. This is the purview of epistemology.

But we need to define truth in the first place before we can start to grasp if it truth is even capable of being known. This is best presented as a parable to start.

After being asked about the nature of Truth by an unruly Ox, an irritatingly clever Goat explained, "The paths of all Truth respond to the Four Questions of the Sages: What do my hands teach me?, What do my memories teach me?, What do my Gods teach me?, and What do my parents teach me?"

The Four Questions of the Sages serve as concise references for four distinct approaches to understanding truth. Each perspective contributes to the totality of our existential experience, forming a reasonably complete picture of truth in every moment.

The first two questions—What do my Gods teach me? and What do my parents teach me?—are external to us, they represent the interobjective and intersubjective elements respectively.

The latter, What do my parents teach me?, represents the systems into which individuals are born or with which they engage. This can be categorised as friends, family, fraternities, and factions. Essentially, any system that can be interacted with directly falls into this category.

The former question, What do my Gods teach me?, pertains to the underlying meaning of these systems, which may or may not be religious.[1] This encompasses the cultural context and internal language that shape our behaviors and expressions within these systems. This cultural aspect, which can be termed as meaning and morality, has the potential to influence the systems identified in the question What do my parents teach me? for generations.

Next, consider the final two questions—What do my hands teach me? and What do my memories teach me? These also represent simplified images.

What do my hands teach me? refers to sensory information: touch, taste, smell, hearing, and sight. This encompasses all measurable phenomena within the empirical realm, categorised as objective knowledge.

Conversely, What do my memories teach me? pertains to the subjective realm, encompassing personal feelings, knowledge, and experiences. This involves the brain and its intangible elements such as consciousness, memories, and emotions.[2]

Together, these four perspectives provide a comprehensive framework for understanding Truth in the world. Although this may seem abstract or mystical, it can be illustrated through practical examples. The body is shaped by the food consumed and the exercise performed (hands), the mind is shaped by the books read (memories), the community is shaped by one's participation (parents), and the immediate world is shaped by activism (Gods). These actions collectively influence and are influenced by the four aspects of Truth, demonstrating their interconnected nature.

This crosses for a moment into metaphysics, but consider a key element of the parable: What did X teach whom? Me. What is “me”? I. Who am I that Truth should impart lessons, moment by moment, experience by experience?

You represent something distinct, unique, and individual. You are something far deeper and more intrinsic, constantly shaped by—and shaping—all four aspects of truth, moment by moment, experience by experience. Everything previously described can be considered a mask, a robe, or a costume. You are not merely your body, your memories, the cultural influences surrounding you, or the systems formed around you. These elements are simply experiences that have shaped you and been shaped by you.

So, what constitutes the “you”? It is something free, capable of experiencing truth through all four paths, yet not bound by those experiences. The robe, mask, or costume can be released at any time. Admittedly, this is easier said than done, but it is possible. This is the essence of understanding that such truth exists and learning to identify how truth is an interplay of various elements to make up our experience in any given moment.

Truth Claims

In discussing miracles as the supernatural precondition for evangelical theology, Dr. Geisler writes that “miracles have doctrinal content. Miracles in the Bible are connected directly or indirectly with ‘truth claims,’ meaning there is a message in the miracle.”[3]

What is interesting to me is not the claim that miracles exist or that they contain a message. What is interesting is that “doctrinal content” is connected directly or indirectly with “truth claims.” Truth claims cross all boundaries of philosophy but they are inherently epistemological.

Many, if not the far majority, of such truth claims are taken through faith or, at the least, as a tested belief on an individual level. If anything, the majority of truth claims are impossible to prove with any certainty. “Every man and every woman is a star” [AL 1.3]. It is a [metaphysical] truth claim. It is not verifiable outside of a faith or presupposition that it is, indeed, true. But in and of itself the concept of every man and every woman as a star is a truth claim that must be accepted as true—a precondition, if you will—for Thelema to be truthful.

That Thelema differentiates and, in fact, delineates very clear lines between individuals must be accepted before its (so-called) “primary tenet”—Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law [AL 1.40c]—can actually hold any merit or weight. Those who believe that this little soundbite is the most important in Thelema have missed (or it would seem they have missed) that there are many truth claims that must first be acknowledged and accepted before that phrase has any meaning at all. Yes, it certainly may be the whole of the Law. Yes, there certainly may be no law beyond it. Yes, it certainly may be something against which no other shall say nay. But until one is clear about their place in this universe, as a star among stars, as an individual outside of any collective notion of power, as part and parcel of God of Very God, there is absolutely no comprehension of what Do what thou wilt should mean in the first place.

On the Nature of Truth

[insert material here]

Four Validity Domains

Any theory of Thelemic epistemology must take into account multiple dimensions that include both objective reality as much as we can interact with it and subjective reality that shapes the manner in which we perceive our inner states as well as the world-at-large. We also have to take into account both systemic structures in which we function and the cultural environment that shapes our underlying assumptions. This offers up four validity domains.

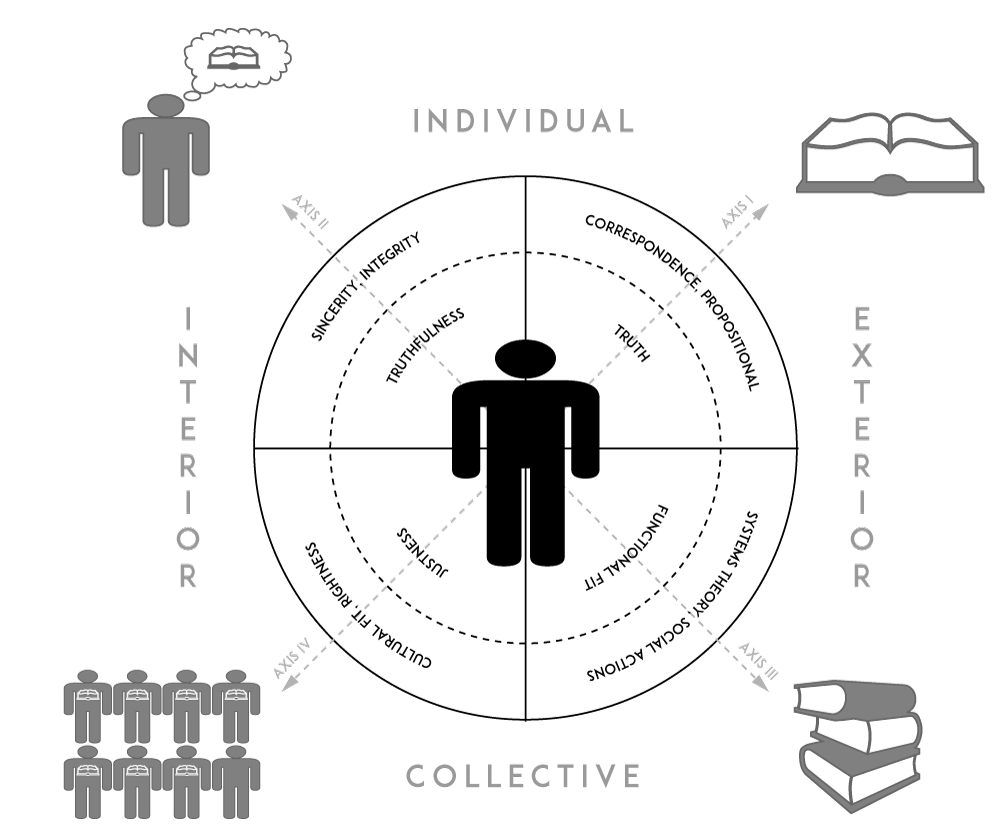

Borrowing a breakdown from Wilber's AQAL modal,[4] we find these four domains to be objective [Axis I], subjective [Axis II], interobjective [Axis III], and intersubjective [Axis IV]. All entities [Stars] and experiences [point-events] inherently have these four validity domains from which we can explore our assumptions about individual and collective perceptions of reality.

We will continue to come back to this approach multiple times as it is far more elegant a solution than many others.

Something that comes up a lot in occult spaces is this idea of the “Right-Hand Path” and the “Left-Hand Path.” For most of occulture's modern history, these have been fixated on moral justifications for diametrically opposed ideologies and praxes. The Left-Hand Path is little more than Twinkies for angsty teenagers. The Right-Hand Path is just another name for those who prefer rules and regulations over experience and can't seem to keep their noses to themselves.

Wilber offers a different view of these “paths” in light of the AQAL model I've just referenced. It is a far more balanced look that escapes the moral view and squarely places these “paths” into a more useful understanding. We can see this in the diagram above that the “right-hand” side is all exteriors. These are surface elements that we see in a broad view (span). We measure these things—even when they are just ideas or theoretical. The “left-hand” side is all interiors. This is the material we have to interpret (depth).

Granted, there is some crossover between them—as any model is just that, a model, not a perfect representation of reality. But the point stands here that Right-Hand and Left-Hand are both necessary for a balanced approach. We cannot have one without the other.

Thelema is neither a “Left-Hand Path” nor “Right-Hand Path” philosophy or religion. It is an integral philosophy and religion. It is both individual and collective. It is an individual belief and a cultural worldview, and it exists within various systemic and structural elements.

Epistemology as Self-discovery

It is important when we talk about the Great Work that we are clear about one of the most basic elements of that work itself. Crowley succinctly puts it this way: “Let him, before beginning his Work, endeavour to map out his own being …”[5] This is a clear and direct call for introspection and personal archaeology in such a way that it leaves no aspect of the individual uncovered. It is the epitome of self-discovery.

Self-discovery, the fundamental state of Thelemic epistemology, centers around experience; not what one might learn from any given experience but in the experiencing the experience itself. The epistemological foundation of Thelema is about the love (unity) and innate joy with each expression of the moment and in our direct experience thereof. “Remember all ye that existence is pure joy.” [AL 2.9a]

(unfinished)

Attribution

No part of this publication may be used or redistributed for any purpose without the express prior written consent of the author.

Canons of Thelemic Philosophy & Religion © 1996-2024 by Qui Vident.

Comments

If you wish to comment about the materials here, feedback is welcome. Feel free to email questions, comments, and concerns regarding the Canons to curate@quivident.co.

These phrases of the parable itself are mnemonics. They are not to be taken too literally. ↩︎

But even the stuff that we have begun to “see,“ like, memories and emotions and ... stuff ... are all still interior to the brain matter that is exterior. We cannot touch/taste/smell/hear those or, quite frankly, see them (yet) in any real way. We can only experience them personally. Hence the difference between “hands” and “memories” in this parable. ↩︎

Geisler, N. L. (2005). Systematic theology. Bethany House Publishers. p. 49, italics in original. ↩︎

Wilber, K. (2001). Sex, ecology, spirituality: The spirit of evolution (2nd ed.). Shambhala Publications. ↩︎

Crowley, A., Desti, M., & Waddell, L. (1997). Magick: Liber Aba. Weiser Books. p. 145. (emphasis mine) ↩︎