Religion

Introduction

Religion, as such, has become one of the largest boogiemen of Thelema since Crowley proclaimed calling Thelema a religion might as well be "a rather stupid kind of mischief." There is some wisdom in that statement when you see the kind of approach that many take toward Thelema today either in the course of a superstitious faith or in attempting to narrow down "academic" discussions of religion to the level of magisterial legitimization.

The exploration of Thelema as a religion is a topic that requires some delicacy of approach.

Classification of Religion

Despite our Prophet’s need to muddy the waters and rain confusion through many of his own personal expressions of Thelema, there is no reason to doubt the explicit words of the Book of the Law on the matter. He was quite correct in his letter on religion, found in Magick Without Tears, that the Book of the Law does not, anywhere, include the word religion. However, almost all—if not, in fact, all—of the elements that are common with religion can be found within the two-hundred and twenty verses of our most holy book, not to mention the rest of the Class A materials that many consider to be within the Thelemic Canon.

Defining Religion

Religion can be seen as something "extremely meaningful or [as an] integrative engagement."[1] By this he means that religion is something that "is a particular functional activity [in] search for meaning, truth, integrity, stability, and subject-object relationship."[2] This could mean just about anything. Wilber admits this when he suggests that while some might balk at this definition—even though there is a great deal of common sense to it—they usually come to an understanding of the definition when an example of science as Einstein's religion is provided (though this example from Wilber is spurious at best given Einstein's deep religious devotion) or, alternately, that Star Trek's Spock held logic as his religion (a better, if fantastical, example). This definition of religion does not require any supernatural inclination or institution. It is more in the nature of a search or a journey than a specific discovery or a final destination.

Philosophy is made up of three primary avenues of study with dozens of secondary and tertiary avenues that extend outward from almost every branch of knowledge. Metaphysics is the study of where we are. Epistemology is the study of how we know. Ethics is the study of what we do.

Religion seeks to answer many of these same questions, though it usually does so through some divine revelation. Various religious factions have used everything from blind faith to strict reason to examine the questions, but all come back to a very similar divine premise within at least metaphysics which tempers the rest of the examinations from thereon out. However, whatever else religion may be, I posit that at its most basic religion is a praxis between the individual and something deeper than himself and generally a manner in which these communicate in some form or fashion. Most of the aspects of religion that overlap with philosophy should be considered philosophy. The aspects of praxis should remain in the purview of religion.

In the study of religion there is the thought that religion, as such, is a construct of specifically Western sociological examination and is not a "real" category of human phenomenon. This is a valid concern, of course, and one that should be taken seriously. It just so happens to be the subject of the first topic here: the classification of religion.

What do we mean when we say that something is a religion? How do we define that concept? Despite some discussion to the contrary—and we’ll see some of that in a moment—religion has been consistently defined through broad strokes for centuries.

One of the earliest formal definitions of religion comes from Friedrich Schleiermacher who defined religion as "das schlechthinnige Abhängigkeitsgefühl"—which is commonly translated as "the feeling of absolute dependence," though there is some contention as to whether or not that should be "the absolute feeling of dependence."[3] Not too long after, Friedrich Hegel, in what could be interpreted as a one of the nearest foreshadowing of the metaphysics of the Law of Thelema, submitted that religion "is the Divine Spirit’s knowledge of itself through the mediation of finite spirit."[4]

While it is not my intention to survey the entirety of definitions of religion here, I think it is important to see both the diversity and the similarity of definitions over a span of centuries. I will quote a few for examples though I won’t be deep diving into any of them specifically here. It is merely important to note that while they have some differences between themselves—and will have some differences from the definition I use here—they have a congruency between them that all point in the same direction I am headed with my own thoughts.[5]

James Frazier wrote, "By religion, then, I understand a propitiation or conciliation of powers superior to man which are believed to direct and control the course of nature and of human life."[6] William James states that religion is "the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider the divine."[7] Following up from there, Durkheim published a definition of religion that stated, "A religion is a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say, things set apart and forbidden – beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community called a Church, all those who adhere to them."[8]

Later we see two definitions published that move into the area of religion as symbols. Thomas O’Dea proposes that "Religion, like culture, is a symbolic transformation of experience."[9] Then Clifford Geertz, coming at religion as both a symbolic and cultural system as well, says that religion "is: (1) a system of symbols which acts to (2) establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men by (3) formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and (4) clothing these conceptions with such an aura factuality that (5) the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic."[10] Catherine Albanese agreed with this in her definition that religion is "a system of symbols (creed, code, cultus) by means of which people (a community) orient themselves in the world with reference to both ordinary and extraordinary powers, meanings, and values."[11]

I have left out two definitions to which I will return in a moment, but I will end the litany of definitions here with the submission from Fredrick Streng that "Religion is a means to ultimate transformation"[12] to which Joseph Adler tacked onto the end a very appropriate "and/or ultimate orientation."[13]

By now, even if I have belabored the point, I think it is clear that religion is a complex topic and there is no single definition that is conclusive or "right" in the way it approaches the subject while also seeing a continuity of similarity through all of these definitions.[14]

In the late 19th century, Edward Tylor suggested that the "minimum definition of Religion [is] the belief in Spiritual Beings."[15] Yet in that same work, Tylor provides this "minimum definition" through a specific examination of those who question the legitimacy and existence of religion at all. The idea mentioned previously, that religion as a construct of examination, is not a new idea. It has been with scholars for some time now.

Timothy Fitzgerald claims that "there is little or no agreement among academics on what religion is or is not."[16] I think the brief examination of definitions above shows that agreement is not about uniformity of specifics but about consistency in the broad strokes. Fitzgerald believes that religion is a subversive category that stands apart from the idea of the secular, dividing the examination into power games. While that is partially accurate, we find such definitions as Durkheim, and agreement from Albanese, that do not make any separation between the ordinary (secular) and extraordinary (religious). Are we bound to such ideas and power games? I submit we are not.

In approaching my own look at religion—and Thelema as a religion—I gravitate toward two specific definitions.

- The first is from Paul Tillich[17] who stated that "Religion is the state of being grasped by an ultimate concern, a concern which qualifies all other concerns as preliminary, and a concern that in itself provides the answer to the question of the meaning of our existence."[18] I have yet to find a more theologically and functionally accurate definition of Crowley’s "True Will" than Tillich’s own "ultimate concern."

- The second definition, and the one around which the rest of this section is generally designed, is from Gerd Theissen, German Protestant theologian and New Testament scholar, who states that "Religion is a cultural sign language which promises a gain in life by corresponding to an ultimate reality."[19]

It is from here we move into an examination of the character of religion and tie that back into one approach to the nature of Thelema as a religion. To be sure, this is not the only manner in which to examine the subject, but it is one that disregards institutional claims and avoids a dogmatic approach to such a sensitive subject.

Three Characteristics of Religion

Religion, in general, appears to take on three characteristics that transcend type or mode.

Semiotic Character

Religion, as a sign system, is primarily made up of three specific expressions: these are myths, rites, and ethics.[19:1]

- Myths explain in narrative form what fundamentally determines the world and life. Myths, as I have stated in the past, is not a matter of something that is a lie, but a truth that is enshrined through a larger pictorial language pattern and applied universally.

- Rites are patterns of behavior which repeat themselves, patterns with which people break up their everyday actions in order to depict the other reality that is indicated in myths.

- Rites are made up of three specific aspects: words of interpretation, actions, and objects. In the words of interpretation the myth is made present in concentrated form. Through them actions take on symbolic surplus value and as signs are related to the 'other reality'. On the basis of this 'surplus value' the objects present in the rite are removed from everyday, secular use—including the places and buildings in which the rites take place.[19:2]

- Ethics is a part of the religious sign language insofar as behavior is integrated into the sign language itself. This is more or less a matter of consistency in norms and values.

Systemic Character

Religion exists within a systemic field as an adaptive shape of social reality. It can integrate into both systems of survival and growth (thriving). It is a motivating system of social relations that exists outside of a specific historical timeframe and yet within the flow of history itself.

The systemic character of religion, however, includes concepts such as authority, meaning, obligations, and any taboos existent that all arise out of aggregated individuals engaged in social construction.

Cultural Character

Religion offers a cultural context for individuals who adhere to the fundamental principles of a given religious community. Religion, much like politics or society, is intrinsically bound up in culture itself. To that end, examining such concepts is a spectrum and not a binary process of in-groups and out-groups within the greater Thelemic community itself. While such an examination does show a divide between Thelemic culture and non-Thelemic culture, such is not the scope of this essay. Part of exploring religion, as a concept, is the exploration of Thelemic culture as opposed to Thelemic cult.

--vv Move All to New Page vv--

Functions of an Authentic Religion in Relation to a Thelemic Expression

It has been said in the past that Thelema is resistant to being defined as a religion in any meaningful way; yet the echo chamber is filled with those who have regurgitated the Victorian spectator sport of pauper, prison, and priest alike. They have taken a piece of Thelema here and a piece of Crowley there and chewed it all just enough to vomit it back up in a manner that is palatable just enough for conventional society outside the insulated fraternities left behind or inspired by the Prophet while hoarding so-called secrets for an elect that could never find its way to offer the world something meaningful to its clear and present concerns. Conversely, there is a world teacher on every corner that would deny the pragmatic asset of a Thelemic worldview by continuing a pseudo-literalism of Crowley’s magical work in a manner for self-aggrandizement.

The very lives of Thelemites on a daily, weekly, monthly level show incredible resilience in the pursuit of the religious inclinations from public worship to private devotion. The New Age Movement influences have begun to filter off and what remains is the same underlying desire, a longing if you will, for the sublime as a personal and meaningful aspect of existence.

While we have seen attempts at religious facade or liturgy through O.T.O./EGC, there has been no serious attempt to explore religious expression outside that limited Victorian occultism of O.T.O. and Gnostic Catholic revivals of the 18th/19th century. Any attempt to break the mold of O.T.O./EGC has been little more than a mimic of the same with tweaks to include "progressive" social elements within the same liturgy or the creation of a close approximation. No true innovation has been made in the area of religious expressions of the Law of Thelema.

Whenever we speak of a Thelemic fidēs—referenced herein as a Thelemic faith in the sense of trust, conviction, or strong confidence, but ultimately as the ground of spiritual origin—we must always presuppose and remember the complex structure of relationships that organize and define that faith: [1] a matrix of historical origin; [2] the lack of and disinclination toward the need for an ecclesial tradition; [3] contemporary and emergent communication; and [4] an uncoerced certainty of truthfulness that continues to examine and learn through intimate engagement with the truth.

There are six important functions to any public form of the Law of Thelema that must be targeted if it is to be vibrantly authentic and sustaining into the future: [1] a sense of personal and communal mystery in religious experience, [2] a worship expression centered around the Law of Thelema, [3] a sacramental reality, [4] a historical identity, [5] a feeling of being part of the entire Body of Nuit, and [6] a holistic spirituality.

Sense of Personal and Communal Mystery

...

Hierologically (or Doctrinally) Centered

Talking about doctrinal stability can be a dangerous and volatile conversation when put out into the public sphere of social media. And yet doctrinal positions are the core of any religion and understanding how doctrine works is important. Also, finally, delineating doctrine from dogma can be difficult but it is necessary to avoid confusion, calcification, and control within Thelema.

The diminution of orthodoxy has been a mainstay of Thelemic, dare I say all occult-oriented, rebellion.

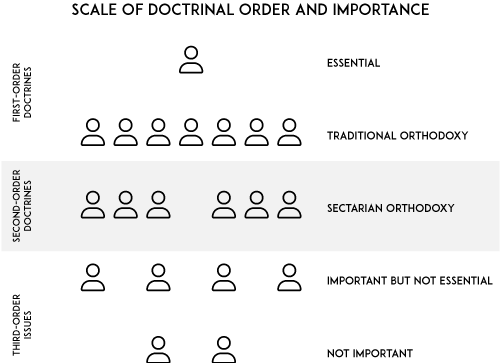

Scale of Doctrinal Order and Importance

While St. Augustine (354-430) is often credited with having written, "unitatem in necessariis, in non necessariis libertatem, in omnibus caritatem" (unity in essentials; in non-essentials, liberty; in everything, charity), it is likely the more recent work of Marco Antonio de Dominis (1560-1624) in his book, De Republica Ecclesiastica.

In the early centuries of the Church, theologians typically only debated what they felt essential to the stability of Church doctrine and tossed the rest. Prior to the 1970s, in fact, the idea of a demarcation between anything other than essential and nonessential doctrines of the Christian community was absent from the theological discussion as nonessentials, such as in the distinction by Meldenius, were generally considered to be anything in Church practice that was not supported directly through biblical injunctions. Quite frankly, the theological landscape of the time did not demand much more than "this is vitally important" and that’s the way we do it"—though the debate on which doctrines should be in which category has raged throughout history.

- First-order doctrines are those hierological issues (or doctrinal issues, if you prefer that phrase) that would include doctrines most central and essential to the Law of Thelema.

- Second-order doctrines are distinguished from the first-order set by the fact that Thelemites may disagree on the second-order issues, though this disagreement may, and most likely will, create significant boundaries between adherents without a loss of identity. When Thelemites gather themselves into organizations and sectarian forms, these boundaries become evident.

- Third-order issues are those things over which Thelemites may disagree (even heatedly) and remain in close fellowship, even within local groups and organizations.

These three categories are important for the pursuit of essentialist (or presuppositional) apologetics.

Sacramental Reality

...

Historical Identity

...

Community Oriented

...

Spiritual Formation of the Individual

...

Sideline Discussions

Gods

See Gods

Aeonic Theory

See Aeonic Theory

Attribution

No part of this publication may be used or redistributed for any purpose without the express prior written consent of the author.

Canons of Thelemic Philosophy & Religion © 1996-2024 by Qui Vident.

Comments

If you wish to comment about the materials here, feedback is welcome. Feel free to email questions, comments, and concerns regarding the Canons to curate@quivident.co.

Wilber, K. (1999). A sociable god: Toward a new understanding of religion. In The collected works of Ken Wilber, volume three. Shambhala Publications.. p. 71. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Finlay, H. E. (2005). ‘Feeling of absolute dependence’ or ‘absolute feeling of dependence’? A question revisited. Religious Studies, 41(1), 81-94. ↩︎

Hegel, G. W. (1895). Lectures on the philosophy of religion: Together with a work on the proofs of the existence of God (J. Sanderson, Trans.). E. B. Spears (Ed.). Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Company. ↩︎

Note that this is an acknowledged bias of using definitions that point to and in support of my own assertions. While I have yet to find any definition that does not support my own conclusions, I recognize that there are definitions that attempt to negate religion as a category of examination rather than redefine it outside even the variety found in these examples. ↩︎

Frazer, S. J. (1911). The golden bough: A study in magic and religion. Macmillan. ↩︎

James, W. (1936). The varieties of religious experience: A study in human nature: Being the Gifford lectures on natural religion delivered at Edinburgh in 1901-1902. Modern Library. ↩︎

Durkheim, E. (1947). The elementary forms of the religious life: A study in religious sociology. Free Pr. ↩︎

O'Dea, T. F., & Aviad, J. O. (1983). The sociology of religion. Prentice-Hall. ↩︎

Geertz, C. (1993). Religion as a cultural system. In The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays. Fontana Press. ↩︎

Albanese, C. L. (2012). America, religions, and religion (5th ed.). Wadsworth Publishing Company. ↩︎

Streng, F. J. (1985). Understanding religious life. Wadsworth. ↩︎

Adler, J. A. (2014). Reconstructing the confucian Dao: Zhu Xi's appropriation of Zhou Dunyi. SUNY Press. ↩︎

Something of note is that many of these same definitions are used repeatedly through various textbooks to show the variety of approaches to the subject. ↩︎

Tylor, E. B. (1871). Primitive culture: Researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, art, and custom. J. Murray. ↩︎

Fitzgerald, Timothy. (2017, August 8). The Critical Religion Association. https://criticalreligion.org/scholars/fitzgerald-timothy/ ↩︎

A large portion of my own theological metaphysics is informed through Tillich’s existential theology. ↩︎

Tillich, P. (1966). Christianity and the encounter of the world religions. Columbia Univ. Press. ↩︎

Theissen, G. (2010). A theory of primitive Christian religion. SCM Press. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎